The oatmeal cream pie on the kitchen counter was a luxury I refused to indulge in, couldn’t indulge in.

One bite and suddenly there was 170 calories down my throat.

One bite and it would change everything I had worked for. One bite and I would lose it.

The oatmeal cream pie would continue to sit there, making a mockery out of me.

But I wouldn’t give in.

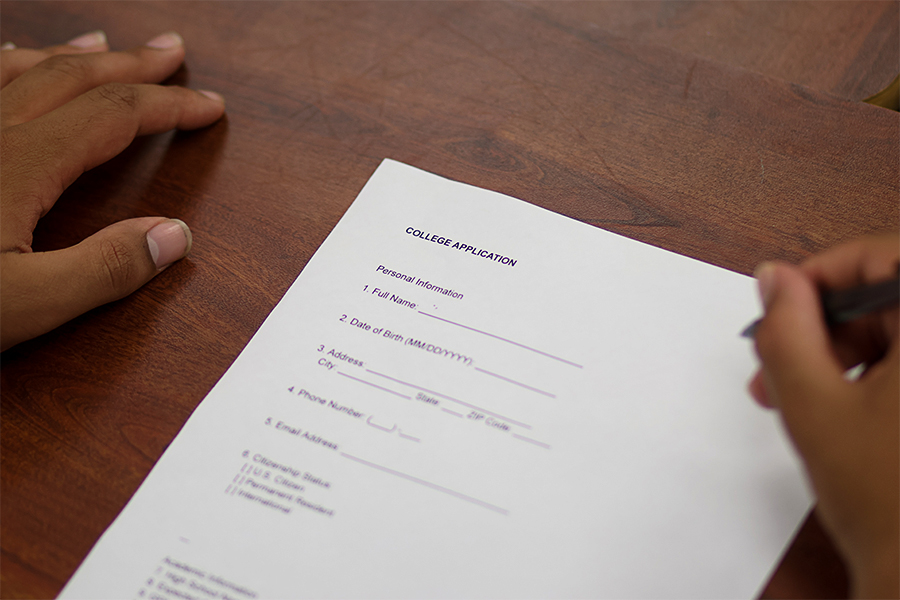

I was 15, navigating my way through the murky waters of high school, drowning in homework and expectations. It was the spring semester of my freshman year, and with every passing day, I grew increasingly hopeless.

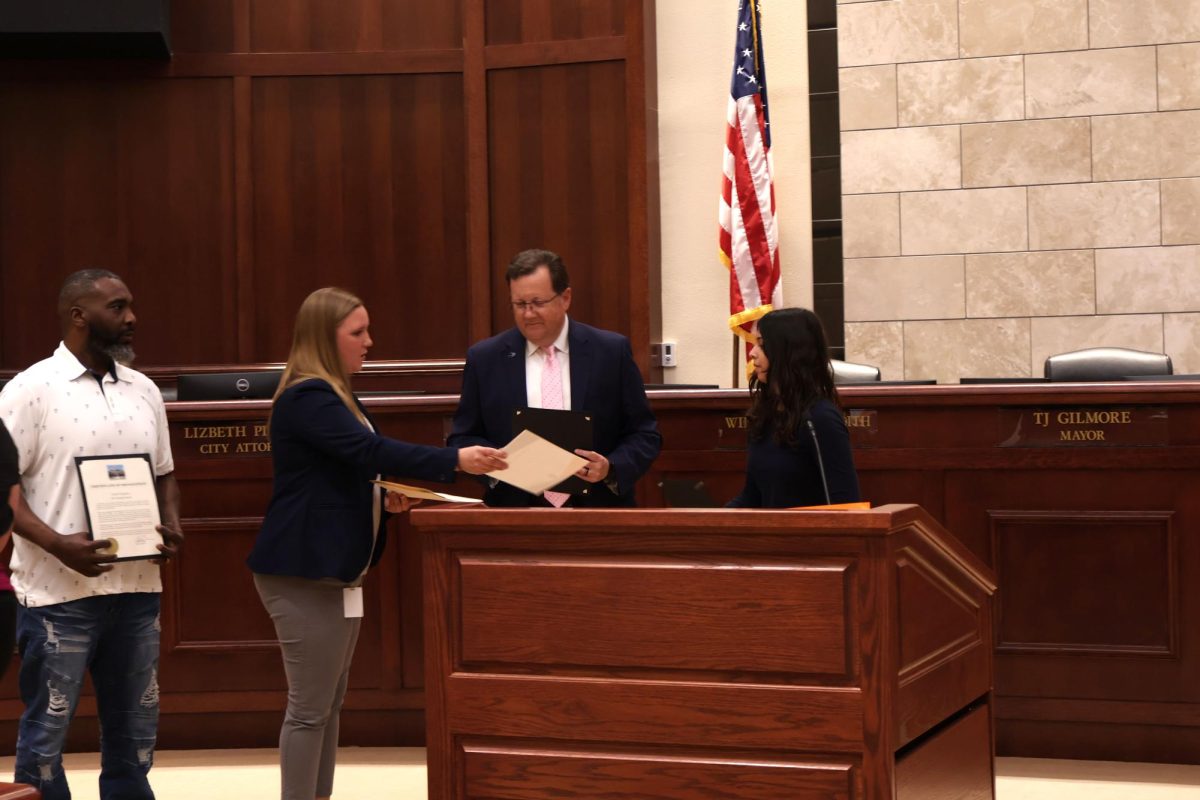

Up until that point, high school had been nothing like what I envisioned. I thought I had it under control. After all, I had been the kid who’d adored school since I learned to read. I was the kid who joined Student Council in the third grade and became president in fifth because self-consciousness and uncertainty were completely foreign to me back then.

I was the kid who wanted to do everything and be everything, and with two parents like two stars in a dark sky to guide me, I felt like I was capable of everything and more. There was no stopping me. Not even when middle school came.

I was gifted. I had potential. The world was my oyster, as the saying goes (although I have no idea what that means). I wanted to be my parent’s golden girl, to change the world somehow.

And for a while there, it seemed like I was on my way toward achieving that. But then high school arrived, and it felt like a slap in the face.

I can’t pinpoint the exact moment I started to feel so useless, so out of control. All I remember is feeling everything either so intensely or not at all.

I got up every morning because I had to. I went to school every day because I had to. Me, the girl who liked school, who got excited about new pens and agendas and color-coding my classes, suddenly couldn’t stand the idea of school, the girl who had it all together all of a sudden had no grasp on her own life.

I walked through the halls of my school in a zombie-like state with my headphones in my ears to eliminate any possibility of social interaction. I read in the cafeteria, not necessarily for entertainment, just because the pages of my books were safer than sitting with people who wouldn’t acknowledge my presence.

It wasn’t so much the loneliness of my own head that scared me, but the fact that all the things I once lived for no longer meant anything to me.

I like to think I disguised these feelings pretty well, because I was still making friends and keeping high grades.

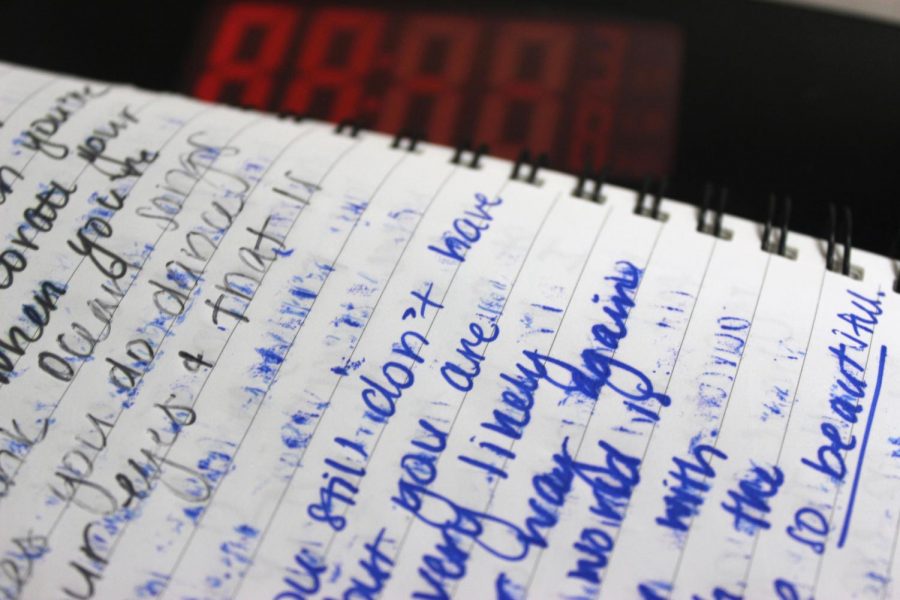

What came after realizing my own misery was a troubling infatuation with food. All of a sudden I was struck with an obsessive concern for what I put into my body. I was hyper-aware of everything I ate, and it made me sick.

I needed control. I needed to take back my life and figure out how to change this pattern, to find my way out of the abyss I had fallen into. In my twisted and frail state of mind, I decided the best way to cope with my reality was to stop eating altogether. I thought achieving a tiny, thin figure would somehow transform me back into the happy-go-lucky girl I once was.

I didn’t stop eating immediately, it was progressive. I started by skipping a couple meals here and there, water being my beverage of choice. I ate practically nothing for breakfast, skipped lunch and didn’t really eat a meal until I got home for dinner.

Once at the dinner table, my task was a difficult one: getting through the meal. Finishing an entire plate was too difficult, so I always made sure to leave plenty of leftovers on my plate. I was mortified of the potential weight-gain.

The fear of eating went hand in hand with my new obsession for the scale in my mom’s bedroom. I had to keep track of the things I did eat in a day and make sure it didn’t interfere with my goal: being skinny.

The weeks that followed consisted of continuous starvation and skipped meals. The lunches my mom prepared for me every single morning with so much love and care went uneaten. Too afraid to throw away the food, I always made sure to try and give away the food before giving up and coming home with all the contents of the bag still inside.

I was consumed by guilt, but at the expense of being thin, I had to sacrifice the lunches.

“Awe, you’re so small!”

“You’re so skinny.”

These comments were only fuel to the fire.

I felt like I had to keep up this persona, like people knew me solely because I was thin, like all that mattered was my size.

But I was exhausted. I was so tired of disappointing the people I loved, of coming home and seeing the look on my sweet mom’s face when I brought another day’s worth of lunch home completely untouched. I was tired of the chronic headaches and ignoring my growling stomach.

I was just so tired.

I was thin. I should’ve been content, proud even, that I achieved what I had wanted for so long. But I wasn’t. All this weight gone, and I was still not happy.

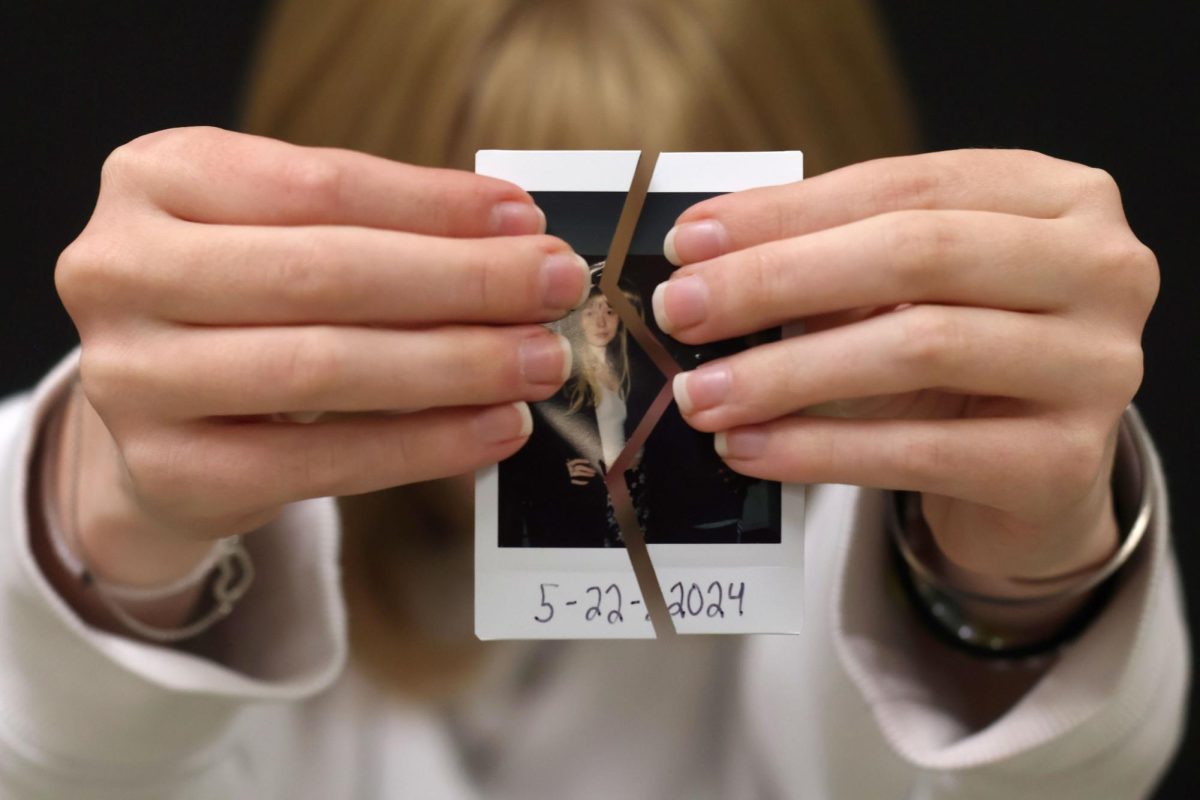

It was then when I realized: I wasn’t alive, I was merely existing.

I wanted more out of life. I didn’t want to starve, I didn’t want to be a walking skeleton anymore.

To say it took a while is a ridiculous understatement, but slowly I did it. I picked up the oatmeal cream pie on the counter and I ate. I put away the scale, I gained back my healthy weight.

The pain of starving myself as a method of recovery taught me a multitude of lessons. I came to understand struggles don’t have a look. The reality is we are all struggling and recovering from something. We all have our own perception of the world, and 99% of the time, we all live in this exclusive world inside of our heads.

But I know now that there is nothing wrong with that. Getting better is a lot like having a bruise: it gets worse before it starts to heal.

For me, opening up was the painful part. It was debilitating to admit to myself the reality of my mental state, how much I despised who I was. It was a reality I refused to see, but when I realized what I was doing to my body, it hit me. I needed recovery, and I needed it in a way that wouldn’t deteriorate me. My recovery came in all shapes and sizes, found in the most unexpected places. My recovery came when I could be by myself and I didn’t feel alone. My recovery came when I could enjoy a meal with no fear or guilt.

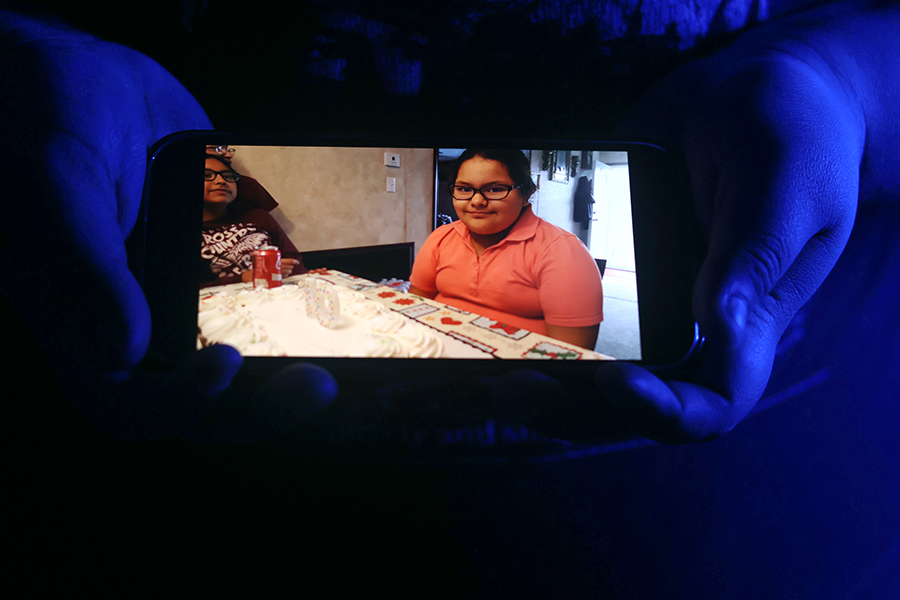

The biggest lesson learned was that food was not my enemy. Food was there at the end of every long day, the dinner table being the place where we all got to catch up and talk about our day as a family. Food was there when I went on my first date with a boy I love.

Food doesn’t have to be a scary thing. Food is a component of my life, but like all things, it does not define me.

Only I get to define myself.

Sofia Barnett • Jul 2, 2020 at 8:38 PM

I LOVE this. Beautifully and brilliantly vulnerable. I am so so proud.

Laure • Jan 23, 2020 at 11:25 PM

I love this piece. I know it took a lot of hard work to get you to tell your story but I know many people can possibly relate in someway. I’m so proud of you love!