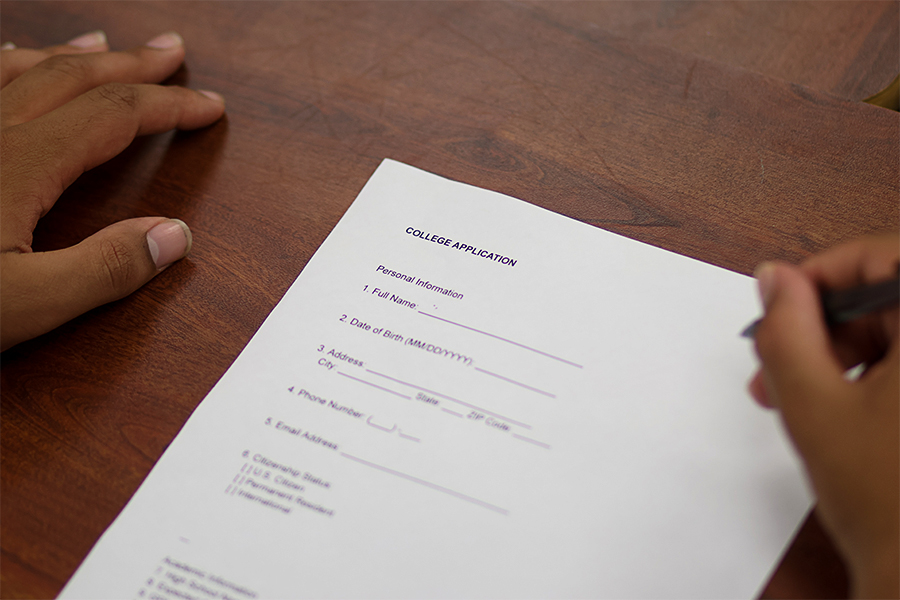

When I was born in Arlington, TX, I was officially a U.S. citizen, but as I grew older, I knew the color of my skin could and would be my worst enemy. Seeing my mother struggle to speak even an ounce of English – a language she did not fully understand yet – was the hardest thing to see as a 6-year-old girl, who freshly came back from Mexico.

Going to school in the United States seemed like a dream to others; it meant the ability to have a better education and a better life. But my life was the complete opposite. When I was in elementary school, I thought the teachers would treat me with care and respect, considering the fact I was new to the school and the country – the country I didn’t know much about and only heard of through movies and television. Everyone at that school treated me differently, like I was an alien from a different planet. I had no friends, nor adults I could trust inside that building. Everyone had it against me because of the color of my skin.

I had difficulty learning the English language when I was little, causing the bullying to get even worse from both students and teachers. I also had this problem where I had trouble asking the teachers to use the restroom. Every single day, going to the school nurse’s office, having to ask for a spare change of pants – “Oh, you’re back?” the nurse said with venom in her voice. I realized the nurse had an annoyance toward me and with any Mexican-American kid who walked into the room. Having to explain to my mom or grandma what had happened every day – seeing their faces as they frowned and even tear up, was the saddest thing I have ever seen.

I would have to hear them lecturing me on how I need to speak up and stand my ground – not letting people push me around like I was invisible. “Ponte las pilas, mi gordita, y tú puedes hacer lo que tu deseas en el futuro.” (Focus, my princess, and you can do whatever you wish for in the future.)

There was a point in time where the bullying went from bad to worse.

Little boys would say “He has a crush on you.” Then, they would run away laughing, and the boy who apparently had a crush on me looked at me with such disgusted eyes, and the response would always be the same – “Ew, never.”

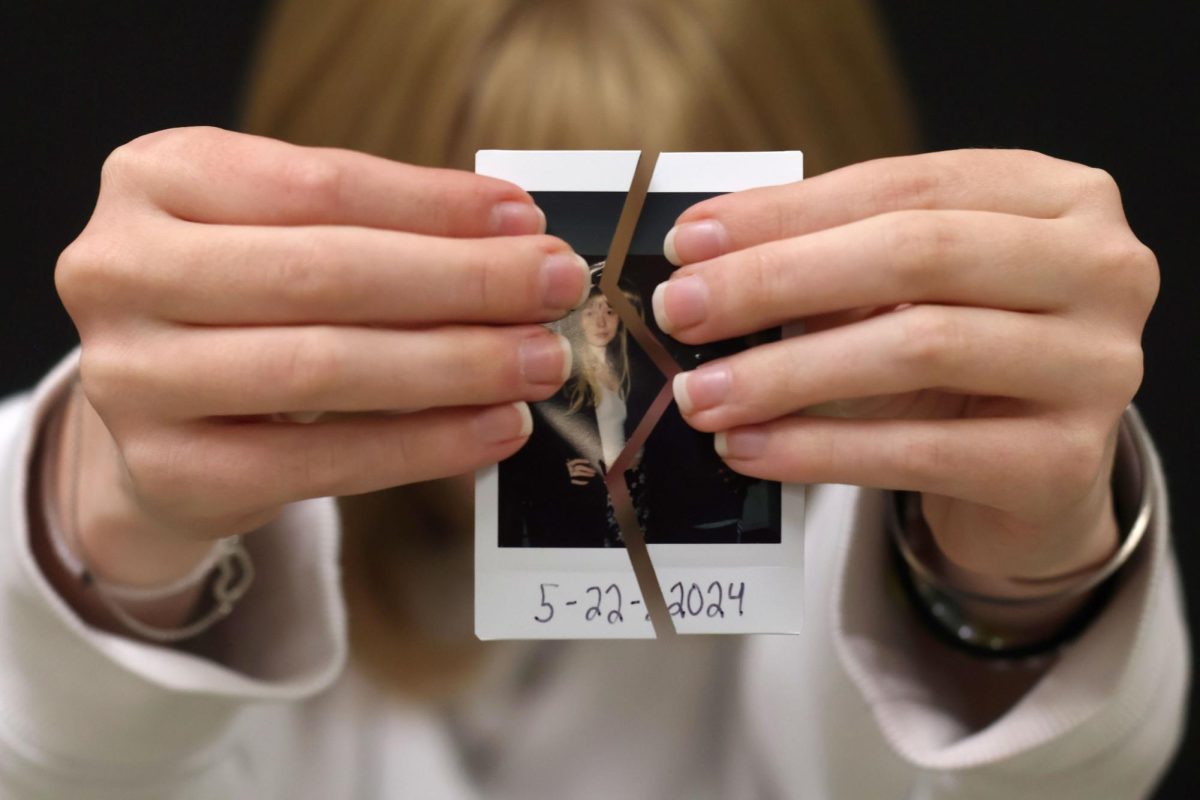

Little girls would pull my hair which was most of the time just ponytails and buns. My mom and I called them tomates (high bun) or cebollas (low bun), it was just something we said to laugh and giggle. I remember crying after school in the bathroom because I always had a small bald spot from where the girls would yank on my hair. I even had my arm hairs pulled out, “Eww you look like a monkey!” or “Do monkey noises!”

I wanted to get far away from this place. I wanted to go back to Mexico and be where I fit in, where everyone looked the same and no one judged each other. I felt so safe and loved in my native land.

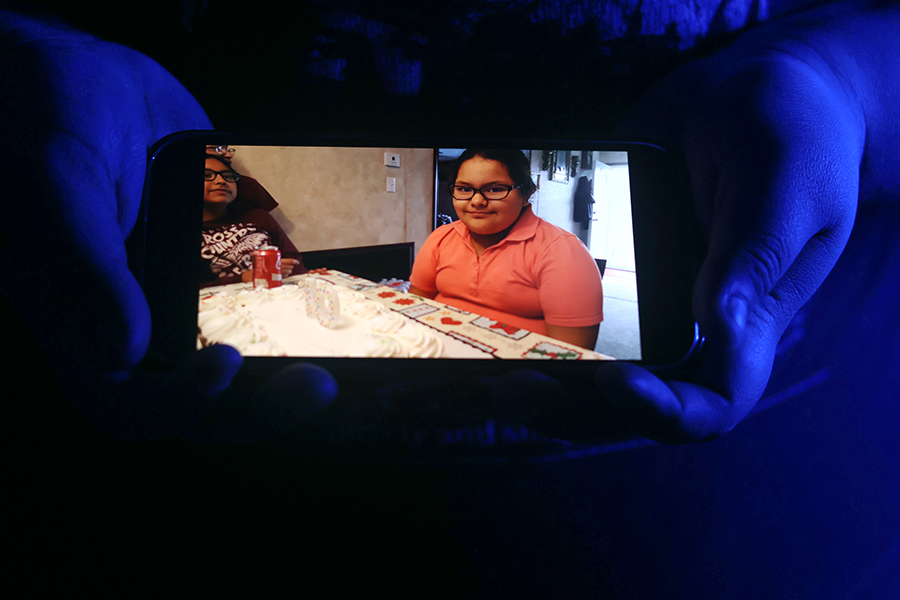

When I still lived with my grandma in Mexico, we used to go back and forth from Nuevo Laredo and Durango, where my mother, aunt and everyone I loved grew up. Whenever I came to visit, I saw big letters carved into the brick arc. El 21 De Marzo, which is the day the small village was founded and life bloomed inside of it.

My excitement was always off the roof because everyone knew me as “La cuata’s daughter” (the twin’s daughter as my grandmother was supposed to give birth to twins, but one passed during childbirth). I always owned up to that title; I didn’t mind it at all. I actually really liked it. My sister always jokes around that everyone knows me and they “kept a photo of me in their wallet.”

Being surrounded by such a rich culture and comfort from loved ones strengthened me and my self-esteem. Later on in life, I wasn’t embarrassed about being Mexican anymore. I’m proud of my heritage, my family and my country. I would never trade it for anything else.

Que viva Mexico. (Long live Mexico.)

Samantha • Oct 21, 2024 at 9:36 AM

Viva Mexico!!