Column: Finding a true identity

‘We shouldn’t be restricted to the ‘other’ box.’

My palms were sweaty and my body shuddered as I hesitantly walked into my new classroom for the upcoming year. I glanced around the room filled with unfamiliar faces and sat at my table. Eager to kick off my second grade year I began talking to my new classmates, when one of them suddenly asked what my race was. The peculiar question scared me, so I told them I wasn’t sure, and then proceeded to be embarrassed and awkwardly laugh. I wanted to make friends so I joined in on the joke about me; I was the fool and let them laugh.

After I got home I went to my mom with tears streaming down my face. I explained how embarrassed and hurt I was to be the face of the joke. My mom tried to explain I’m a mixture of many ethnicities and that’s what makes me special. She said I’m Asian, black and white, but she also said those races alone don’t define me. I have more races and ethnicities that make me who I am.

But I didn’t care to know about all my other races. I just wanted to know the “one” race that defined me so kids wouldn’t call me out.

The question “What am I?” lingered in my mind.

I didn’t know who I was; even my family didn’t have a clue as to all of my ethnicities. They called me a mutt, joking that I’m just a mixture of everything. A year later I was reminded about this all over again during my first standardized test when I was required to fill in a box to distinguish my race.

Throughout my mom’s time in school, she didn’t know her race either. Administrators even pulled her aside to ask, but she didn’t know so she wasn’t able to give an answer. They ended up writing on documents that she was white. She was labeled white because of her father, but her mom was Japanese.

Why do legal documents require us to pick one race when so many individuals identify with multiple? In middle school, a teacher once told me to just pick a race and stick with it.

But I needed answers. I continued to question myself.

I was told by family that I’m Asian but deep down inside I knew I was more than just Asian. At school I continued to be singled out. I brought a bento box to lunch and because of that, classmates regarded me as fully Asian. I would explain to them I’m more than just Asian. They didn’t care.

So finally all the years of being curious got to me. I had to get answers.

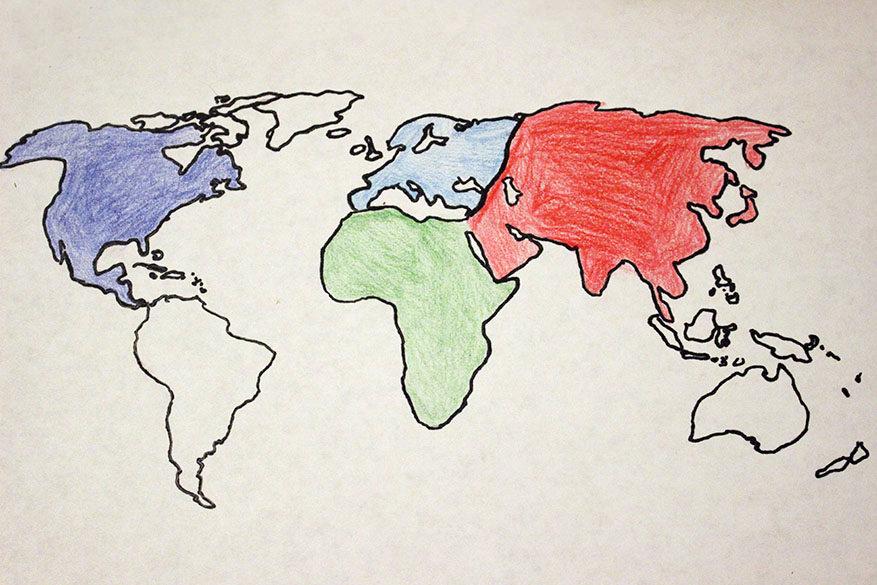

Soon before sophomore year began I looked up DNA tests online, purchased one and then anxiously waited one month for my results. Finally I had an answer: 26 percent Asian, 20 percent African, 17 percent British and 15 percent French. The other 22 percent comes from different parts of Europe.

The Asian and French results were not a surprise because I grew up in a Japanese culture and my dad has always said he and I are French. However, the African did catch me off guard. My mom and dad have always said I’m African, but we didn’t think it would be such a high percentage.

Although I am made up of more than just one race, I’m so used to telling people I’m Asian. My mom has always said to never forget about my other cultures because I have more influences in my life through them. Documents shouldn’t make us pick just one race as lots of individuals are mixed with several. We shouldn’t be restricted to the “other” box.

Elva Beauchamp • Dec 1, 2017 at 1:47 PM

Very good! I’ve always hated those boxes, too (and I am considered white). I usually won’t even fill them out and we all are different! I love your article and so proud to call you nephew!

Grandpa John • Dec 1, 2017 at 11:17 AM

Great points Noah. You have a sharp mind and a talent for writing. I love how you express your thoughts and draw in the reader in your journey. You make the reader feel a part of your feelings and make us want answers too. Your writing makes the reader question and that is the beginning of knowledge. Keep it up and I am looking forward to the next article and one day a book. ?

Wendie Smith • Nov 30, 2017 at 7:24 PM

Awesome job, Noah. I am so proud of you and the young man you are growing up to be.